In June 2022 I flew to Queensland to meet aboriginal people. I wanted to find an aboriginal community and learn about indigenous culture. I was studying social work at Deakin university and was learning about how to approach aboriginal communities. I wanted to see how my theories I was learning at university worked in practice.

I travelled to Queensland without knowing which community I was going to go. I had learned to approach with a not knowing attitude. I thought going to a place without planning to be there was an appropriate way to enter a post colonial community and displaced people. I flew on a cheap air carrier because I was using my remaining student allowance while on my semester break.

I caught a plane to Brisbane. Then caught the Spirit of Queensland, north to Gympie. Gympie had experienced major floods two months earlier. As disaster relief was included in my training Ibthought Gympie would be a good place to start because I could kill two birds with the one stone. I text a friend from my past while travelling on the train. They arranged their son to be waiting at the station and the opportunity to stay at his house. On the way I struggled to see visible signs the township had experienced floods. There seemed little chance of post disaster response practice. However, on the drive Guy, my friends son told me about a mens shed at Cherbourg. I had studied Cherbourg at university and understood the aboriginal cultural significance of the township.

We drove home to Kilkivan, 40 minutes SouthWest of Gympie, in the Black Snake area. I learned later it was Wakka Wakka country. The next day I called and arranged visiting the mens shed in a couple days.

Guy drove me and participated in woodwork the first day. I met an aboriginal man, a brown water man called Wayne. He was supervisor of the Cherbourg Mens Shed. It was appropriate for me to work with Wanye. I told him about my experience with Mens Sheds, though I didn’t tell him about my long wish to go to Cherbourg which began at university. understanding about I began my journey to work with and share knowledge with aboriginal people, by sharing woodwork skills.

Over the following three weeks I shared more knowledge. I shared when I was ready. Though I had the feeling I should of explain who I was and what I was doing at the beginning I learned that Wanye had many western ways and stressed many things too. His position was precarious and not necessarily a certain thing.

I learned more about the nature of knowledge at that time too.

I learned that knowledge can come as a shock – seem sudden, not logical, and new knowledge can make earlier knowledge a mistake.

to the system, and some of the differences between white man knowledge, and important

On the way, they mentioned Cherbourg was near home (40 minutes SouthWest). When I studied Cherbourg at university I had always thought Cherbourg was significant because I remember the emotion of my favourite lecturer, when she spoke about Cherbourg. I took this as good knowledge.

I left for Cherbourg the next day.

The morning I arrived at the site I felt welcomed. I met Wanye and he began his initiation. Wanye was an aboriginal man. And he was a brown water man (not Wakka Wakka). He had started the Shed 5 years earlier. Wanye believes he has been successful in starting the shed on wakka wakka country because he is not from Cherbourg or from the same mobs who attend and therefore did not obligations or owe others which he would had. Wanye believed having obligations would have made it impossible to have had the power required to run a machine workshop. Power was required to set the rules and regulations required to keep the shed safe. Many of the men were low skilled and many of the machines were He says he is not restricted by mob commitments.

Wanye told me he is the last generation of the stolen generation. I reflected that he means he feels interdependent at Cherbourg, and toward wakka wakka people. In other words, he has come to Cherbourg because it has a history of many mobs existing in the one place. Furthermore, he is saying Cherbourg is a place for aborigines which dont have another place or country. Moreover, he came because he identified with Cherbourg as a key instrument for the stolen generation.

I was welcomed at the site. Everything worked out good. I stayed for several weeks. I tried to be as respectful as a could of aboriginal culture. I met many aboriginals. I shared a lot experiences and enjoyed learning about cultural exchange. There were many challenges. I completed several woodwork projects. I feel I nade many errors, however the aboriginal people were friendly. attended there for the next two weeks.

I found accomodation in Murgon at the main hotel. Murgon is 7km from Cherbourg. History had separated the two towns. My accomodation supported pokies which seemed to extort the aboriginal community. I reflect that racism exists between the two towns. The was an eerie feeling on the streets of Murgon of a culture war. In comparison, the streets of Cherbourg felt like stepping back in time to a forgotten era. Cherbourg was like a model town such as a hollywood re-creation. I was waiting for a surprise. I was enthralled with the place, entranced, and extremely curious. I continued to come back even though I was frustrated with the way Wanye ran the Shed.

Wanye and I discussed many things over the two weeks. Wanye talked to me about aboriginal issues. He also talked about personal issues with me. I learned that stories are intertwined with both personal and political matters. A major challenge was my sense of urgency which had carried over from my time at university. At the Aboriginal Shed relationships were more important than material work.

The man I stayed with at blake snake drove me on my first day. He was a bit depressed and stayed for something to do. It was significant that I had come with a younger white man who seemed depressed. I think it was recognised that I had knowledge about a younger ‘brother’ who needed to hear elder knowledge. He was engaged to stay and worked on a project with Wanye. He came back the next day too.

One rule at the Shed is that each person has their own project and work space. There were projects which had not been finished and had sat on the bench for a long time by the dust that sat on top. I reflect that this emphasised the importance of possession. Post colonial oppression had dispossessed indigenous people therefore nothing was going to be taken from them at the aboriginal shed.

I visited the Ration Shed on my last day. I spent the time reading the time line, in its entirety. Nakita the aboriginal women who greeted me there expressed that she was impressed how long I stayed reading. I reflected that tourists treat the narrative as if its about them, and their journey to the place rather than the place which they are given permission to be. The writing was accessible. I didn’t cry until I was close to the end.

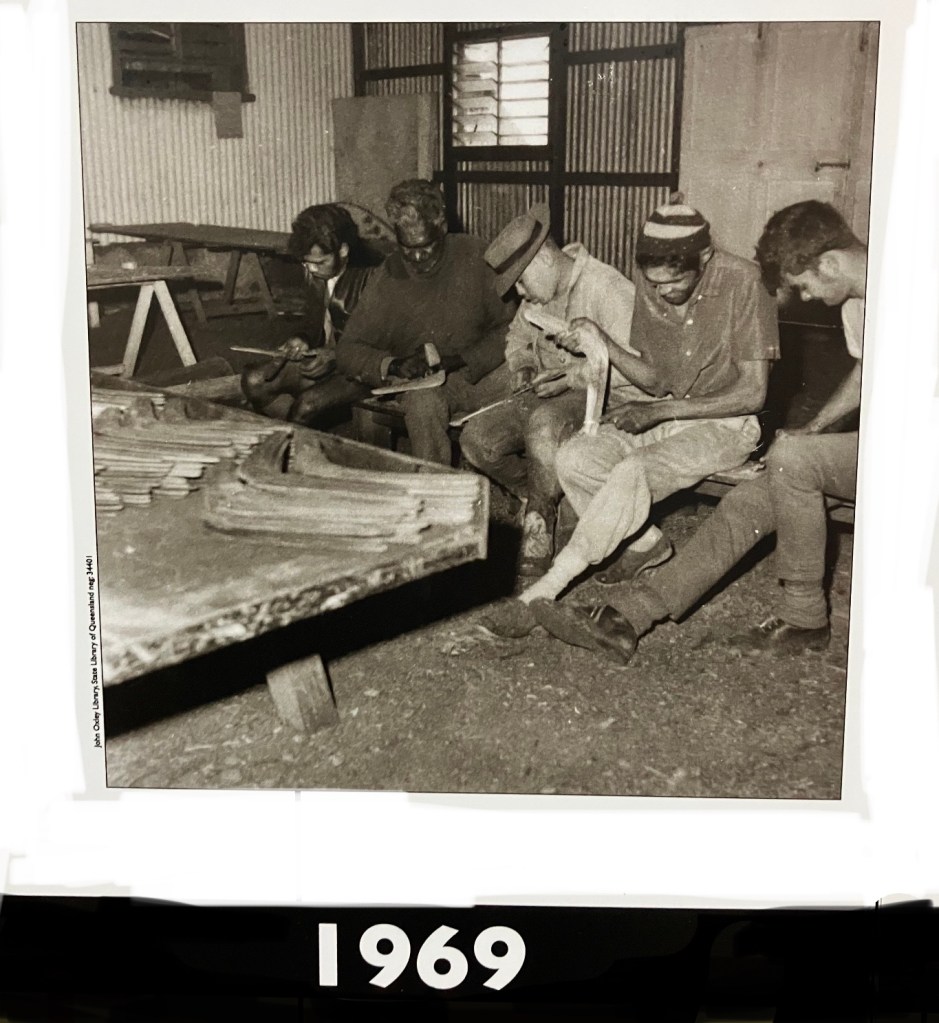

I realised that there was a history to the model of woodworking. Cherbourg had been industrially productive in the past. Woodworking had been a part of the history of the people who lived there. History added context to the way I felt about being there and the idea of a working model of a production line of products was not as far fetched idea as some might think. I had cone across resistance to ideas at a previous white mans Men’s Shed I had worked at. There are ingrained rules in the model which are subjugated for the purposes of some others self interest, feeding their quest for power and privilege. The principle of non profit is not appropriate in all cases.

I wanted to introduce a model I had developed at a previous Men’s Shed working with people with cognitive impairment. The model produces a range of marketable products which can be sold. The working model is based on a simply set of woodworking principles. The mis adaptable to the environment and ficuses on the function of the . It was clear that it was probably not possible to use the model at this shed. I was not allowed to deviate from the way Wanye ran the shed. There was a possibility in the future that something could be gotten.

Discover more from Christiaan McCann | Risks and Solutions for the Vulnerable | Socialwork Projects in Hobart

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.